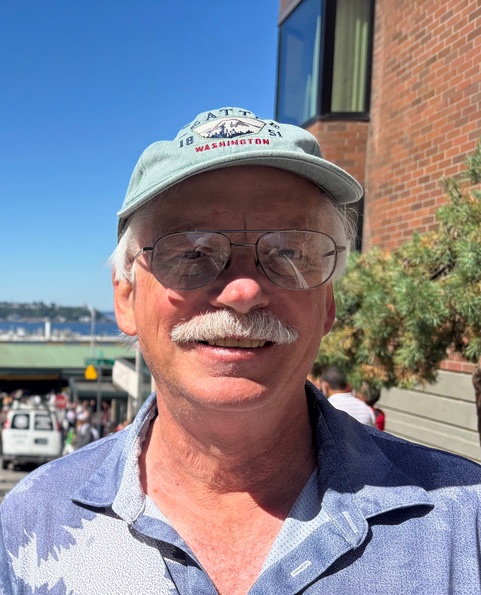

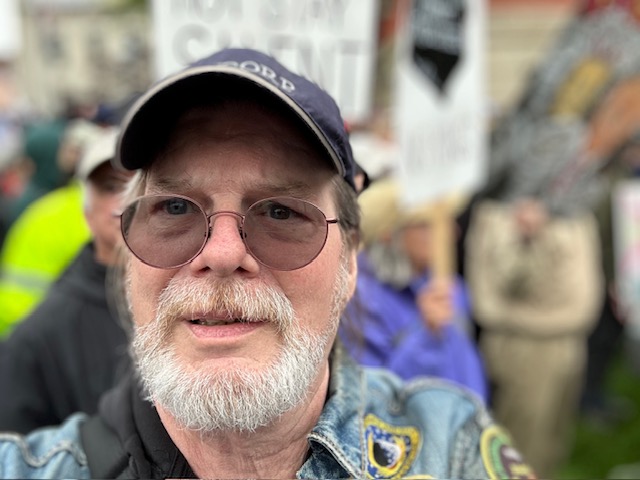

Stephen Case returns to Asimov’s with “The High Shrines”. Read on to learn how his interest in monastic communities influenced this story.

Asimov’s Editor: What’s the story behind this piece?

Stephen Case: I’ve been fascinated by monastic communities and in particular ancient Christian ones like Mount Athos in Greece or St. Catherine’s in Egypt for a while. I wondered what it would be like at a place like that in the near future, after the effects of climate change and the proliferation of AI. I’ve heard from people who have been there that even the monks on Athos have smartphones now, so maybe I’ve overestimated the resistance to technology you’d find there—or maybe that kind of resistance will reemerge in the future.

AE: How did the title for this piece come to you?

SC: In one sense it refers to climbing, as the protagonist does throughout the piece, to shrines or monastic retreats set on a mountain. But it also refers to the central paradox of the story, a revelation that our narrator—and most of Earth’s AI—are unable to accept. I wanted to play with the idea of a belief or a statement of belief that simply doesn’t compute in the narrator’s worldview and how one would react to it. The story was originally called “The High Sketes,” referring to a particular type of monastic settlement, but “shrines” seemed clearer.

AE: What’s your history with Asimov’s?

SC: This is my fourth story in the magazine. Though none of my previous stories take place in this universe, two previous ones are set in my Lattice universe, which also plays with the idea of a religious community in a science fiction setting (though those—”Daughters of the Lattice” and “Sisters of the Flare”—are set in the far future and a very long way from Earth).

AE: Are there any themes you find yourself returning to?

SC: As mentioned above, I seem to currently have a preoccupation with traditional Christian monastic communities—groups of people held together by bonds of chastity, poverty, and obedience to a hierarchy. It’s a way of life that seems quite foreign today. I’ve never visited such a community, so perhaps it’s easy to idealize, especially based off the readings of Christian mystics like Thomas Merton or the Desert Fathers. But I like imagining how those priorities and lifestyle choices would play out in extreme settings. In some ways, it seems like the kind of self-discipline and self-collection needed by monastics would be ideal for the harsh settings of imagined exoplanets or, in this piece, a strange near-future Earth.

AE: What’s your process?

SC: I get up quite early each morning six days a week and spend time drafting longhand in notebooks. It’s a slow process, but I try to touch my projects every day. Once I have enough material for a piece (or I fill a notebook) I transcribe it, and that’s the first step in the revising process.

I wanted to play with the idea of a belief or a statement of belief that simply doesn’t compute in the narrator’s worldview and how one would react to it.

AE: How do you deal with writer’s block?

SC: With patience, ideally. I let the story go and work on something else, which for me usually means my non-fiction. If I’m up against a deadline and don’t have the luxury of time, I go for a walk. I try to distract myself to see whether my subconscious will put the pieces together for me while I’m not looking. Sometimes it works.

AE: What are you reading right now?

SC: I’m reading a lot of texts in the history of astronomy for a non-fiction book project. I’m trying to tell the story of astronomy’s history in a way that integrates astrology with sympathy for how it was practiced in the past and the genuine influence it had on astronomy’s development—without crediting its use today. The book should be out next year from Reaktion Books. Besides that, I’m reading the latest collections by Theodora Goss and Samantha Wells.

AE: What are some past careers you’ve had and how have they influenced your writing?

SC: I’m still a college professor. I think it’s influenced my writing because I spend a lot of time considering how I can explain concepts clearly and succinctly to a room full of young adults who may or may not be engaged or invested. When I teach physics, for example, I’m considering analogies and metaphors as much as I am equations. I find myself using similar tools when I write fiction.

AE: How can readers follow you and your writing?

SC: I’m not very active on it, but I do have a social media account on BlueSky: @stephenrcase.bsky.social. I have a website (www.stephenrcase.com), and you can sign up for my mailing list. I send out occasional updates on my work.