by Jack Skillingstead

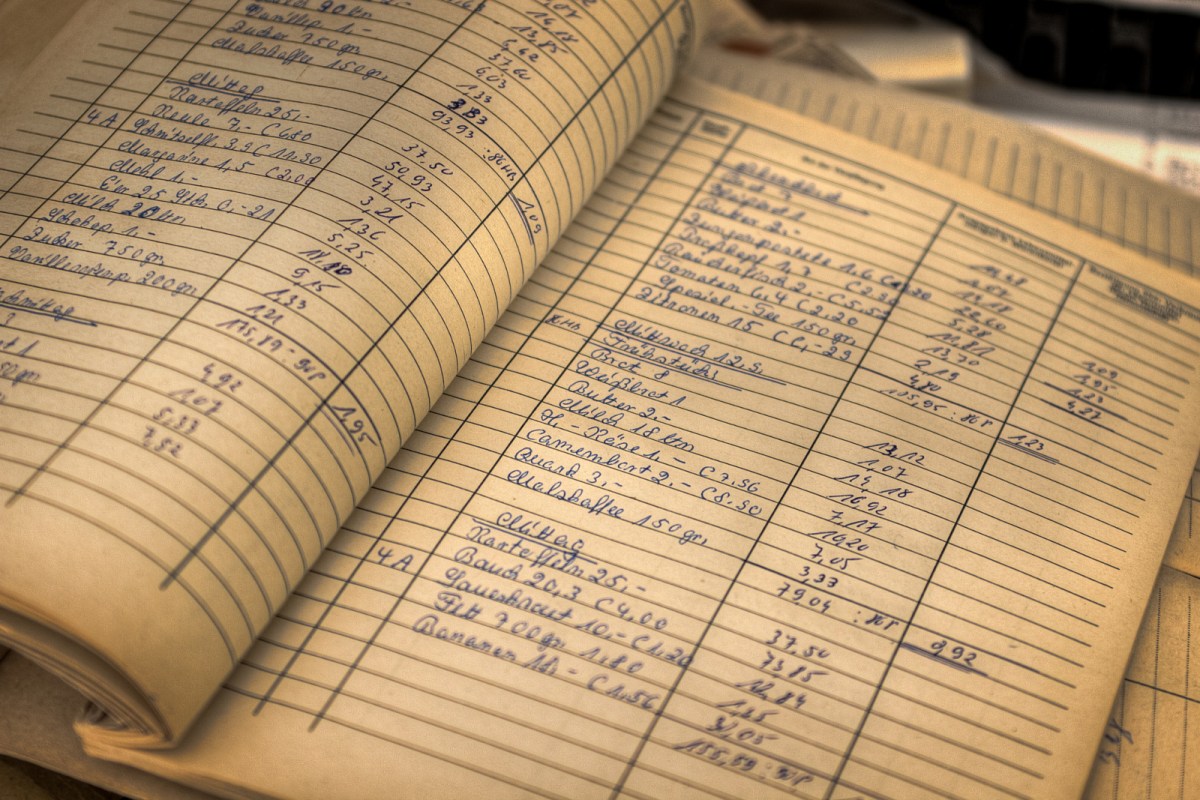

Jack Skillingstead illustrates the importance of persevering through the ever-treacherous path that is writing. Read his latest story, “The Ledgers”, in our [November/December issue, on sale now!]

What happens when a writer has exhausted, or—more charitably—thoroughly exploited his thematic obsession? Three options stand out.

One: The writer presses on, no longer hacking new paths, discovering mysteries and secret connections, but simply changing costumes and performing the same dance over and over until boredom, the marketplace, old age, or a combination of all three turn off the words.

Two: The writer experiments, hoping to discover new ways of exploring themes that have grown stale, ways that don’t feel like retreads, even if it means upending his whole process, stepping into the unknown, and basically being willing to feel lost in unfamiliar territory. This only works if writing itself is an obsession.

Three: The writer quits and finds a hobby to occupy his hours. For instance, single malt Scotch whiskey.

But if it’s me (and it is) then I’m going for number two. For now I’ll confine the discussion to short fiction. I wrote for two decades before breaking into professional print. A big part of what finally got me through the door was my willingness to listen to what my sentences were trying to tell me—this as opposed to what I was trying to force the sentences to tell readers. Conscious control vs letting go. I’ll circle back to this.

I’ve talked before about one of my “Ah-ha!” moments when suddenly (after untold hours staring at sheets of paper and computer screens) I could see which sentences were essential and which not only could be cut but had to be cut. From there it was a matter of working with the remaining sentences, judiciously adding and subtracting, until the idea I’d started with began to emerge on the page in a coherent narrative line. It was still a while before I sold anything. But it was a turning point. (By the way, sales don’t automatically indicate mastery, or even progress, except in terms of craft.) Starting around the year 2000 I used this method to make a lot of stories happen, and from 2002 onwards I sold most of what I wrote.

I hadn’t discovered a story formula or mastered an arbitrary set of rules. Instead I had learned to recognize and abandon narrative ideas that resisted disentanglement. In other words I no longer forced a broken story to “work.” Now, some twenty years later, with a few novels and more than forty stories in print I’ve found myself walking away from half-completed stories, starting new ones then quickly running out of gas. This kind of thing hadn’t happened to me since my earliest attempts at writing fiction. What was going on?

There is an old adage that says writing gets harder, not easier, the more you do it. This didn’t make sense to me when I was younger but it does now. First, this is how it seems to get easier: through daily writing and reading you slowly learn to say what you mean. You gain facility with words. You learn to recognize and cut cliches, and you learn when—and if—to fill the gaps left by their elimination. You learn when to trust your voice and when to doubt it. If you have a decent ear for dialog you learn to not overdo it. If you have a tin ear you learn how to work around your limitations, compensating with narrative acceleration, among other things. And eventually the pages accumulate.

But now, late in the game, I’d been handed the Three Option Problem. During the desert years when it felt like I’d never make that first sale, let alone have a career (however modest), I occasionally flirted with option three. The lesson I’d learned then still obtained: I was constitutionally and psychologically incapable of Not Writing. If your brain is programed to insist you write, then there is no way out of it—at least not in my experience. I’m like a guy ceaselessly treading water. As soon as I quit treading I sink like a stone.

So. Option Two.

There is an old adage that says writing gets harder, not easier, the more you do it. This didn’t make sense to me when I was younger but it does now.

Back in the spring of 2023 I was struggling with a new story. The “idea” was essentially a milieu, a vaguely eastern European city enduring a bleak winter of perpetual war. I loved the opening. An ordinary citizen of this unnamed city-out-of-time is crossing the plaza on his way to the government building where he works when he is waylaid by a spooky guy I thought of vaguely as the Devil, or maybe a minor demon devoted to exploiting violent impulses in people. After that I wrote a scene where my guy discovers a body that has been savaged by a feral dog. These two scenes were connected by an information-heavy (i.e. boring) scene in the man’s office.

I had no clear idea what this story was about. I pushed on for weeks, trying one thing and another, all of them dead ends. I gave up on it a few times because I could not convincingly make the images tell a story. They were fascinating, those images, and disturbing. This story-that-wasn’t-a-story had the surrealistic juice of nightmares. I couldn’t let it go, though in the not too distant past I certainly would have.

Earlier I mentioned learning to abandon narrative paths that “resisted disentanglement.” The many incomplete drafts of “The Ledgers” were chock full of tangled narrative paths that begged abandoning. Every time I tried to push a logical sequence to the next logical sequence, the story resisted. It felt a little like it had decades ago when I regularly forced stories to be stories. Failed stories, but stories. “The Ledgers” worried me. I didn’t want to go backwards as a writer. But neither could I drop the story as a failed experiment. There was something there begging for expression.

It’s good to finish things. As a writer it’s essential that you finish things even if the finished thing ends up irreparably broken. That’s how you grow. Over many years I’d learned to tell the difference between necessary and unnecessary sentences. But “The Ledgers” was teaching me something new, presenting me with a trove of moody horror-infused images straight from the unconscious, images that resisted all my conscious day-world attempts to organize them along what I think of as traditional narrative lines. I decided to follow the dream logic of the images wherever it led, even if I didn’t understand it.

Damon Knight used to tell student writers to “trust Fred.” Fred was what he called his unconscious mind. Okay, I was determined to trust my own Fred. Damon wrote a whole book of story-writing theories that only started with the unconscious. But for my experiment in dream logic I wasn’t going to pay any attention to his or even my own daylight thoughts about telling stories. In other words, I wasn’t going to make the images tell something to readers; I was going to allow the images to discover their own secret connections and show them to me. If you’ve ever awakened with a vivid and apparently nonsensical dream still glowing in your brain and then over coffee or scrolling news on your phone suddenly realized what the dream meant (oh, yeah! The three legged German Shepherd is my dad!) , then you know what I’m getting at.

And it worked.

“The Ledgers” revealed itself with very little conscious effort on my part. After that, it was up to my daylight skills to provide the necessary craft decisions. Writing this story was a revelation. To any new writers out there I say: Trust your dreams…and your nightmares.