by Adam Ford

Australian poet Adam Ford shares the long and erratic journey he is taking to get from finished manuscript to self-published crowdfunded specpo chapbook. Stay tuned for more of Adam’s poetry that will appear in a forthcoming issue of Asimov’s.

Sometimes you have to carry your creative projects with you over many years. Don’t let anyone tell you getting a book out into the world is easy or straightforward.

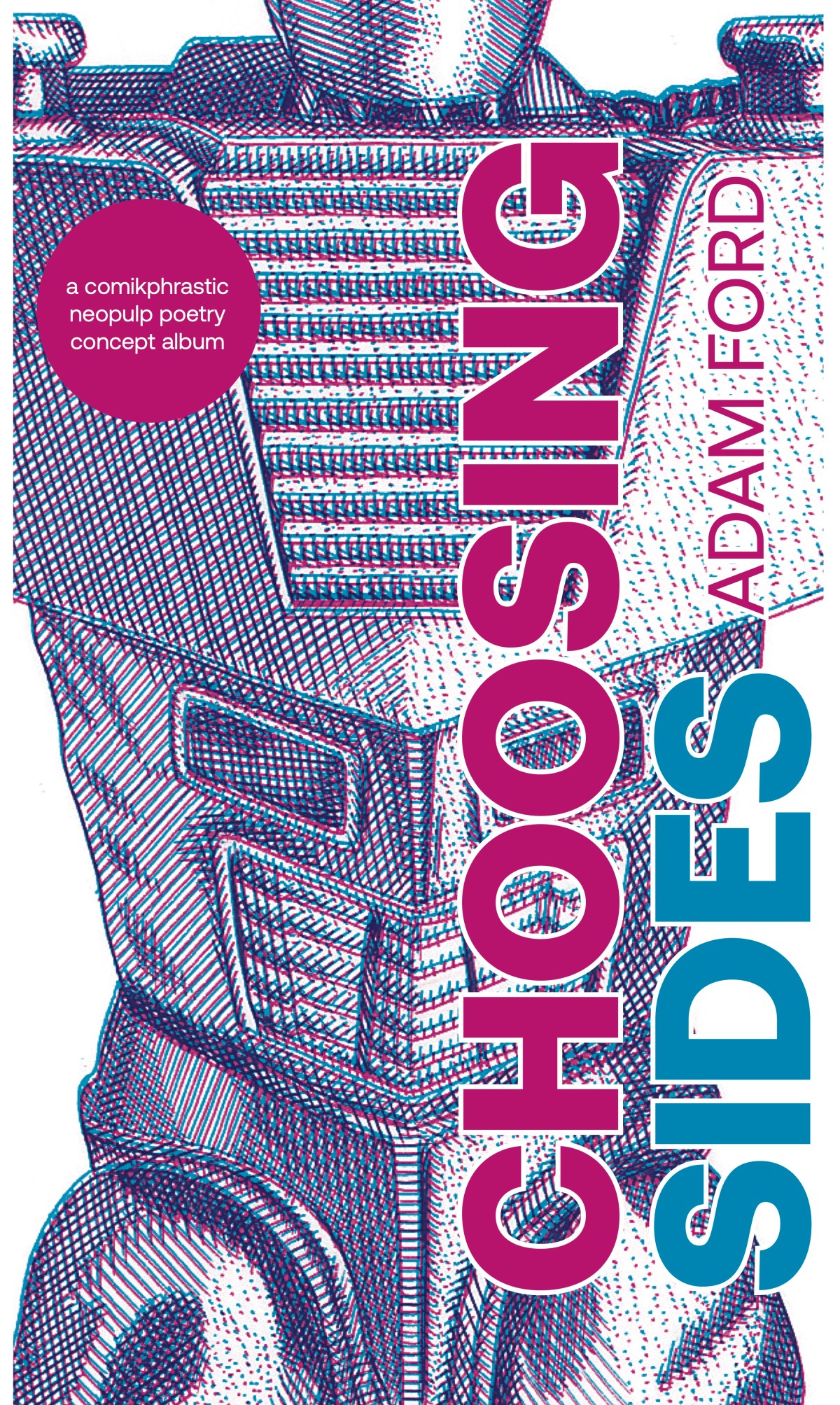

After completing work on a labour of poetic love that saw me write 79 poems in response to each and every issue of the comic book Rom: Spaceknight, I am now on the cusp of bringing a selection of those poems into print as Choosing Sides, a speculative poetry chapbook I am currently running a Kickstarter for to cover production costs

A quick recap: some years back I set myself a sort of morning pages task where I would read a different issue of Rom: Spaceknight, a heavily-B-movie-influenced 1980s superhero comic, for 79 days (one day for each issue of the series), then write a poem about that issue and then publish each poem online as it was written. You can read more about the project in my previous blog for Asimov’s.

Long story short: I did it. But after I had tidied things up and honed those 79 poems into a 33-poem draft manuscript I was faced with the question: How do I turn this manuscript into a book?

I’m not saying what follows is actually the answer to that question, but here’s what came next for me.

1. Pitch it

The logical first step was to find a publisher. My approach to this involved sending poems to journals while also sending the full manuscript out to publishers.

I had some success placing poems in journals including Strange Horizons, Star*Line, FreezeRay Poetry, cordite and the wonderful Asimov’s Science Fiction. But while journals were quite welcoming, finding a publisher for the manuscript was harder.

I searched online for journals and publishers and made a list of ones that seemed a good fit in terms of aesthetics, poetics and the work they published. Here in Australia there isn’t a lot of awareness (or publication) of speculative poetry, so I extended my search overseas. For whatever reason, the field is much more fertile in the US. My research identified about half a dozen publishers in Australia, the US and the UK, a mix of speculative publishers and poetry publishers who seemed inclined toward experimental writing.

I sent the manuscript out one publisher at a time. Often it would take months, sometimes even a year to hear back. Responses ranged from “this sounds interesting” and “thanks for letting us read your words” to “we only publish a few books a year, which limits our acceptances” and the occasional “actually we’ve decided to shut the press down because it’s so much work and we’re really tired”.

One publisher even said, “we liked it but decided it was too niche for us,” which felt like an achievement. When an independent Australian publisher of small runs of poetry collections calls your writing “niche”, it makes you stop and think. Part of me wondered if it was a front cover blurb in waiting: “TOO NICHE FOR US—[name redacted]”

2. Give up

Persisting in the face of well-meaning rejection is exhausting. I had often wondered if my attempt to smash together the joys of pulp science fiction tropes with the precise language and deep personal insights made possible by the poetic form was something nobody but me wanted. Two years of thanks this is lovely but not for us was starting to make the answer seem like ‘quite possibly’.

When the next kind-worded rejection landed, I ran out of puff. I decided to stop sending the manuscript out. I still liked the poems, but my failure to get anyone else to like them enough to publish a book of them made me seriously consider packing the book away and finding something else to write about.

Around that time I caught up with some poet friends at a book launch. It doesn’t take poets long to get to the “are you working on anything?” part, and it wasn’t long after that I was telling a dear old friend about my decision to ditch the manuscript and my feeling that I had made a mistake spending so many years on it.

She listened quietly until I didn’t have anything more to say. The story told, we joined the rest of the launch celebration and talked about other things. For the rest of the night, though, and a long time after, I couldn’t stop thinking about how my story had seemed to make my friend really sad, and how sad that telling it had made me, too.

At first I had thought I was sad because I made my friend sad, but I realised that was only part of it. I also realised I wasn’t sad because I’d taken an artistic gamble and failed. I was sad because I was giving up on the book I’d worked on so hard for so long. That sadness was telling me something: I wasn’t ready to give up. And if I wasn’t ready to give up, I would have to make the damn book myself.

4. Self-publish

Confession time: I’ve actually got a lot of experience making books. I’ve worked as a book editor. I’ve edited and published literary journals. I’ve been making zines for decades. So I know how to put a book together. I also know how much effort it takes. That’s why had been keen for someone else to publish my book. But since no-one seemed to want to make it for me, it looked like it was going to be me after all.

Persisting in the face of well-meaning rejection is exhausting. I had often wondered if my attempt to smash together the joys of pulp science fiction tropes with the precise language and deep personal insights made possible by the poetic form was something nobody but me wanted.

Most of the times I’ve worked in publishing I’ve been on the editing side of the room. The part of making books I have the least experience with is working with printing companies. Fortunately, a comic artist friend had recently run a successful crowdfunding campaign for a comic about AI and art, and was happy for me to pick his brains (i.e., steal his ideas). His comic ended up being a lovely thing to hold in hand, and he was really happy with the printer he’d worked with. I asked him to pass on the printer’s details and got in touch.

Whenever I don’t know how to approach something that involves working with other people, I just come clean about my ignorance and ask a lot of questions. I sent the printer an email that basically said “me poet help make book you how”. They were incredibly helpful, showing me how to prepare a request for a quote they could respond to. They also explained how to prepare a design-ready layout they could work with that would take full advantage of their printing services. So I got the quote from them and I was on my way.

The rest of the production process was more familiar territory, which also involved reaching out to friends and colleagues for help. I hired a friend who is an experienced book editor to proofread the manuscript. He is also a manuscript reader, and offered some good suggestions about the structure of the book as well as checking for typos and consistency.

I reached out to another old friend who is a beautiful pen-and-ink illustrator and proposed commissioning a cover and some interior illustrations. To my joy he agreed and we spent a fun few months back-and-forthing over his illustrations of action figures and toy guns before we settled on something we were both happy with.

Finally I hit up my brother, a book designer and art director, to pull everything together into a print-ready design file. And with that, the book was ready to be made. The only thing missing was the money to pay the printer.

4. Find the money

Not done with stealing ideas from my comic artist friend, I yoinked his crowdfunding plan as well. Based on the quote from the printer and the costs of the cover and proofreading, I set up a campaign on the same crowdfunding website my friend had used. I kept things simple, mainly offering one or more copies of the book, with a couple of hail mary pledges for people to commission a poem or host a private reading from the book.

Assembling the pieces and parts of the campaign was straightforward, though it took a bit of time. The written pitch was easy, and setting up the site was easy too—the website gave good guidance. The sticking point was the video pitch, which took a lot of stuffing around to get recorded and edited in my spare time on my bodgy laptop using a free open source video editor called OpenShot (recommended) and the minimal skills I could remember from a course I’d done ten years earlier. But I got there in the end and the campaign was built. The final step was to submit it for review before going live. This is where things got a little weird.

The crowdfunding site offered a critical review of your campaign and advice about improving it. My comic artist friend had spoken highly of the advice he’d been given, so after submitting the project for approval and getting the green light, I signed up for an online consult.

Life being what it is, the day of the consult arrived and I almost forgot about it. I logged on five minutes late and wasn’t surprised when nobody was there. I emailed an apology and rescheduled the meeting, booking an appointment an hour after the one I missed. But when I logged in again, nobody showed. I contacted the company to apologise again and ask for the best way to reschedule. I waited a week for a reply.

While I was waiting, I looked over the website more closely. Most of the projects on their homepage were from a while back. I couldn’t find one less than 12 months old. Something was going on. My gut told me it was quite possible the company had quietly collapsed without decommissioning its website or any of its automated processes. I reached out to another friend who’d run campaigns on that platform and asked if he thought I was reading things wrong. He took a look and came back saying, “Yeah that doesn’t look so good.”

With no reply forthcoming and nothing concrete eventuating from my online searches for the fate of the company, I decided to find another crowdfunder and avoid the risk of running a campaign through a zombie website. I copied all of the bits and bobs I’d made across to Kickstarter, a larger and more well-known outfit that was definitely looking like a going concern.

It was easy to rebuild the campaign and send it for approval. Until I hit another snag. Kickstarter told me my use of the word “preorder” was against their policies. Because they don’t guarantee the success of any campaign, and because things don’t happen unless you meet your funding goal, technically if someone pledges to help me make the book, they’re not preordering it because if the campaign doesn’t succeed, they won’t get the book. It’s a fair point.

Revising the written part of the campaign was easy enough, but I had also said the word “preorder” about half a dozen times in the video. I had struggled to put the video together, and the prospect of going back and changing something so hard-won was daunting. After a bit of procrastinating I sucked it up and managed to chop out most of the p-words without massacring the video, though I ended up having to re-record the intro.

Edits done, I resubmitted the campaign and got the green light within 24 hours. I had given myself 60 days to raise the funds I needed, so it was time to press the start button and get hustling.

5. Do the hustle

As of this writing there’s about two weeks left in this eight-week campaign. Most of my promotion over the last six weeks has been online in the form of project update videos and on-camera readings from the book shared on Facebook, Instagram and Bluesky to reach a mix of friends, fellow poets and fellow nerds.

I’ve also been reaching out to the people who were supportive of my Rom poem project back when I was writing and posting them online, asking them to help signal boost the campaign. I’ve designed and printed promotional postcards, handing them out to friends and leaving them in cafes and bookstores (and the occasional bus stop). I’ve tabled at book fairs, read from the book at poetry open mics and appeared on my local community radio station. And throughout the whole thing I’ve been checking and refreshing my inbox and my DMs and the Kickstarter page every hour on the hour.

It’s exhausting—a fluctuating mix of desperation, elation, despair and hope. Every time someone pledges it’s a kick in the pants. The Scylla within my amygdala says This could actually happen. Every day that the number of pledges stays the same is the other kind of kick in the pants. The Charybdis in my frontal cortex says What are you wasting everyone’s time for?

Somehow I’ve managed to navigate between those extremes (so far) and I’m still standing (so far). I attribute that to the fact that everyone I have asked for help has been amazing. This whole project has reminded me that artistic projects are collaborative projects, and the joy that comes from collaborating with talented and generous people is maybe even the whole point of this kind of thing.

I think the term “self-publishing” is a misnomer. It’s not really something you do by yourself, because in all honesty you can’t. You can’t do it alone, because if you look around you, you’ll realise you’re not alone. You’re surrounded by talent and good will. We all are. That’s the thing that keeps me going.

6. And then…

As of this writing I am 39 per cent of the way toward the funding goal, with 15 days to go. There’s no guarantee I’m going to cross that finish line, but even if I don’t this has been a fulfilling experience.

Having to go to bat for my own writing despite the self-doubt and the generally-stacked-against-you-odds that come with trying to get poetry published has been a hell of a learning curve. I’ve honed my self-promotional skills, worked out how to look at my own work critically, made creative connections and met people who are fans of poetry or speculative poetry or Rom the Spaceknight or comic books (or even, sometimes, if I’m being honest, fans of me).

I may not know what the future holds for my book, but if I look back on its past, there’s a lot I’ve enjoyed and a lot to be proud of and a lot of people to thank for their support.

And if you think Choosing Sides sounds like a book you’d like to hold in your hands one day, I would love it if you helped to make that idea a reality by visiting the Kickstarter page before the campaign finishes up on October 30.

Lastly, thank you for reading this. I wish you all the best for your own creative ambitions. May they come to fruition in the way you desire with however much help and in however much time they need.