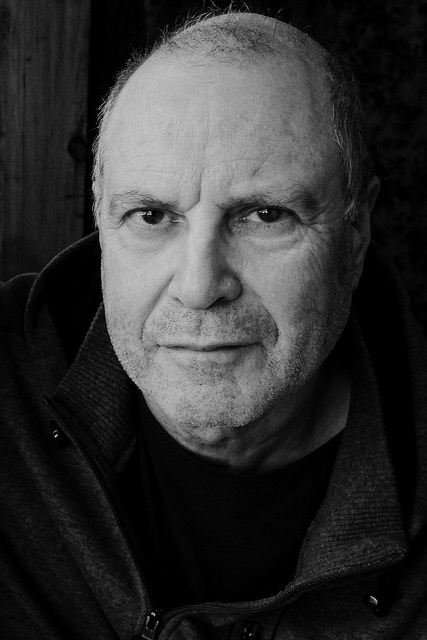

Two-time Readers’ Award winner Ted Kosmatka returns to Asimov’s with”The Signal and the Idler” in our [Sept/Oct issue, on sale now!]. In our latest Q&A, learn all about Ted’s creative process along with how his mother inspired him to write.

Asimov’s Editor: How did this story germinate? Was there a spark of inspiration, or did it come to you slowly?

Ted Kosmatka: The whole thing started as a thought experiment that for a long time I had no idea how to write. All I had was this strange little extrapolation from quantum mechanics that I kept getting tangled up in. You can have a cool scientific idea in your head, but translating it into a story that someone will want to actually read is a totally different problem. In a weird way, sometimes the more excited you are by an idea, the harder it is to write the darn thing, because then you have to write a story that lives up to the idea. Eventually, you’ve got to just start typing hope for the best, so that’s what I ended up doing with this one. It was in my head for a couple years before I managed to write it.

AE: Is this story part of a larger universe, or is it stand-alone?

TK: I’ve actually been wondering that myself lately, as it occurred to me that this story might be in the same universe as a couple other things I’ve written. My old Asimov’s story, “The Bewilderness of Lions” in particular might be circling around the same set of invisible antagonists, if I squint and think about it too long. But I’m not sure. If I ever expand this story into something longer, I guess I’ll get to the bottom of it.

AE: What other careers have you had, and how have they affected your writing?

TK: I’ve had a bunch of jobs over the years. Everything from corn detasseling, to kennel cleaning, to truck stop dish washer, to zookeeper, house painter, math tutor, you name it. The first job where I can remember having health insurance was as a laborer in the blast furnace department at LTV steel. I started off shoveling coke and sinter onto conveyor belts. That job saved me. I eventually became a sampler, and then a tester, working my way up to using this ancient Russian spectrograph machine that broke down all the time. When the company went bankrupt, I found my way into the chem lab at US Steel, and then eventually into a research lab where I got to work with electron microscopes. Later, I started selling stories and moved across country to work in games.

AE: What is your history with Asimov’s?

TK: I started reading Asimov’s magazine as a kid, since my mother had a subscription to it, so that was really my introduction to science fiction and reading in general. Eventually, we also got subscriptions for Analog and F&SF, so between those three magazines, I had access to a pretty steady diet of great stories growing up. Later, after years and years of trying, Asimov’s ended up being my first professional story sale, and I’ve been sending stories there ever since. I used to joke that I could wallpaper an entire bathroom with all the rejection letters I received before making my first sale. I still have a whole drawer full.

You can have a cool scientific idea in your head, but translating it into a story that someone will want to actually read is a totally different problem. In a weird way, sometimes the more excited you are by an idea, the harder it is to write the darn thing, because then you have to write a story that lives up to the idea.

AE: How much or little do current events impact your writing?

TK: My stories are usually based around some twist or weirdness in existing science, so current events tend not to figure into things too much for me. Though with that said, AI has sure been bashing down the door lately, pushing me to get on the wrong side of Roko’s Basilisk, so maybe that’ll change. World events seem to be catching up to science fiction pretty quick.

AE: Are there any themes that you find yourself returning to throughout your writing? If yes, what and why?

TK: For sure, yeah. Every time I write a quantum mechanics story, I think to myself I’m glad I got that out of my system, and then six months later, I am back at it, thinking about some new angle on the subject, so I’ve pretty much realized I’m just going keep writing about quantum mechanics until I die. It’s the mystery that keeps dragging me back. Stories are just a way to think about things and try to impose some sort of structure on concepts you’re wrestling with.

AE: What is your process?

TK: It seems to change all the time. I work a bunch of hours in my day job, so my current process mostly just involves writing late at night when the house is quiet, if I get the chance. I write more stuff than I ever send out.

AE: What inspired you to start writing?

TK: My mom, for sure, was a big inspiration to me. When I was a kid, she was always writing, along with all the other stuff she had to do as a nurse, raising four children, so it seemed to me that writing was an attainable thing that regular people could chase after. It was normal. My dad was an inspiration, too, in terms of his work ethic, all those years working at the mill. Both my parents worked hard and knew how to put the hours in to chase things they wanted to accomplish.

AE: If you could choose one SFnal universe to live in, what universe would it be?

TK: That’s a tough question, since a lot of the best sci-fi stories would be nightmarish to try to actually survive in day to day. Difficult scenarios often make the most compelling stories, but you wouldn’t really want to live in those worlds. The universe of Dune is gorgeous, for example, but I’d have to think twice about picking that one, as my knife skills are lacking. Still, I probably would try to pick something that has humanity out in the vacuum, exploring the vastness of space. Battlestar Galactica, is one possibility. Or Ad Astra. Or maybe Foundation, by Asimov.

AE: What SFnal prediction would you like to see come true?

TK: I’d love to see the asteroid belt mined. I’d love to see us get out there and do some of the things I’ve been reading about for so long. The Expanse series by James S.A. Corey is a great bit of storytelling around that idea.

AE: How can our readers follow you and your writing? (IE: Social media handles, website)

TK: You can keep up with what I’m up to by checking out my website at https://tedkosmatka.us.