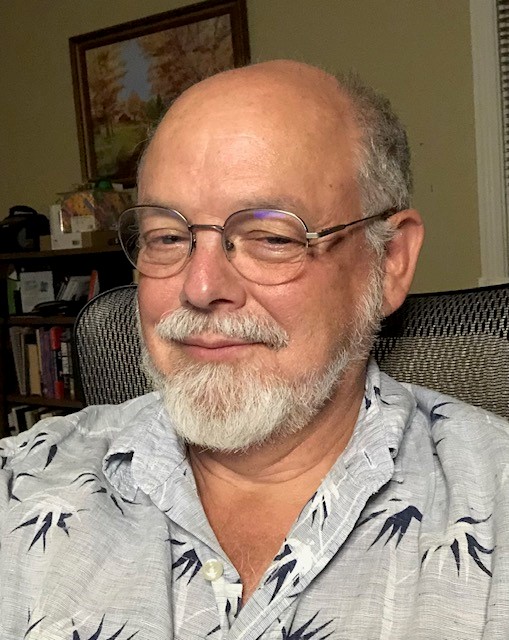

by Chris Campbell

Chris Campbell discusses cosmic horror while pointing to a few examples of how Black authors are pushing the genre forward. Grab a copy of our [May/June issue, on sale now] to read Campbell’s novelette In the Palace of Science

My novelette In the Palace of Science, published in the (May/June 2024) issue of Asimov’s magazine, joins a rapidly growing body of literature by Black writers ostensibly working within the subgenre of cosmic horror. I use the term ostensibly because while these works sit comfortably within the framework of the Afrofuturist movement, their relationship with cosmic horror is considerably more complex. Afro-futurism is a movement that centers on the significance of black people, our history, and our stories. Cosmic horror, at its core, is about the absolute insignificance of humanity and the indifference of the universe to us. As defined, these modes of storytelling, while not incompatible, are clearly in conflict.

There is, of course, another conflict that is readily apparent to those with more than a passing familiarity with the history of cosmic horror: the virulent racism of H.P. Lovecraft, the father of the subgenre. Wrestling with Lovecraft’s more troublesome beliefs is a matter of perennial debate within speculative fiction circles. This debate has spawned numerous essays that do a fine job explaining why so many fans and writers are unwilling to sweep Lovecraft’s work along with his problematic legacy into the dustbin of history. There are also numerous essays and scholarly papers that explore aspects of Lovecraft’s racism, as it appears in his works, in terms of its cultural impact and in the context of the ever-expanding role that BIPOC writers are playing in modern cosmic horror. For the most part, the ongoing discussion about the deconstruction of racism within cosmic horror has been about who is doing it and why it is essential. This essay is not about that, at least not directly. For the few thousand words I have here, I want to explore some examples of how it is being done.

For this discussion of Afro-cosmicism, I’ll explore some of the tools employed by Victor LaValle in his Shirley Jackson award-winning novella The Ballad of Black Tom, Zin Rocklin in their Shirley Jackson award-winning novella Flowers For the Sea, and my story In the Palace of Science.

LaValle wrote The Ballad of Black Tom as a direct response to one of HP Lovecraft’s more openly racist stories, The Horror at Red Hook. Lavelle also dedicates the piece “for H.P. Lovecraft, with all my conflicted feelings.” Within the text of The Ballad of Black Tom LaValle puts his finger on the crux of the conflict Afro-cosmicism has with cosmic horror. A deep and indescribable dread at the notion of an indifferent universe is a luxury only afforded to a person who has not experienced the malice of structural racism.

The prose in The Ballad of Black Tom notably sets it apart from Lovecraft’s work. Lovecraft takes considerable inspiration from gothic writers, specifically Poe. While the quality of Lovecraft’s prose is somewhat contentious, there is no doubt that his style is closely identified with how cosmic horror should feel, evoking an almost otherworldly dream space for the narratives to take place in. In Black Tom, LaValle eschews any indulgence in favor of prose that brings a story set in the Jazz Age into an urgent and present now.

This restraint allows a nuanced approach to characterizing the narrative’s protagonist, Tom, by enabling the reader to notice how Tom employs diction as a method of agency and subterfuge—code-switching at critical moments to adapt to different circumstances and challenges he faces throughout the narrative.

This use of unadorned prose also bridges the Harlem Renaissance with the modern Black Lives Matter era in a manner that offers a damning commentary on America’s progress towards racial conciliation over the previous century.

Tom’s journey highlights this with how it mirrors the Harlem Renaissance—beginning fueled by the optimism of the roaring twenties and ending with a sense of disenfranchisement that uproots him from his hostile native soil. This is a progression similar to the many prominent figures during the Harlem Renaissance who eventually found a greater sense of belonging as ex-pats living in Paris.

Another notable feature of the way the piece engages with the Harlem Renaissance is how it integrates the great migration and the ensuing cultural disconnect between formerly enslaved people and their descendants into the narrative, including how some of the intergenerational divide was bridged, allowing much of the African American oral tradition to survive when it was at the brink of being lost forever. During the Harlem Renaissance, the cultural anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston and the folklorist Thomas Washington Talley were part of a movement to catalog the folklore of the last generation of freed people before it was too late, as they were already well into their advancing years. This persistence of cultural memory after the great migration in a tenuous link in an almost broken chain is replicated in Tom’s relationship with his father, who undertook the great migration. When we meet Tom, he has very little interest in music, a defining feature of his parents. To him, the guitar is little more than another bit of useful camouflage. However, after Tom experiences an awakening, he forms a deep connection with his father through the sharing of music, culminating with the transmission of powerful ancestral conjure music to Tom from his father.

Afro-futurism is a movement that centers on the significance of black people, our history, and our stories. Cosmic horror, at its core, is about the absolute insignificance of humanity and the indifference of the universe to us. As defined, these modes of storytelling, while not incompatible, are clearly in conflict.

The Ballad of Black Tom is a deeply layered work, so a full accounting of its themes and symbols is beyond the scope of a short essay. However, I want to draw attention to two layers we can use to explore the work’s relationship with cosmic horror.

The first is the representation of unrestrained violence the racial caste system encourages and enables. The turning point of the story takes place in the aftermath of a senseless shooting where the victim represents every black person ever shot while holding something harmless. The malevolence of the act is emphasized by the casual way the gun is emptied into the man, only to be reloaded and emptied again. This use of unrestrained violence is returned to in the climax when an entire block of buildings is razed through the use of militarized weaponry. Invoking not only outrages like the Tulsa Massacre, which occurred only a few years prior to the date the book is set in but also more recent atrocities like the MOVE bombing. The two significant acts of violence, along with many of the smaller indignities Tom experiences at the hands of the police, are the real source of horror in the story, not the eldritch abomination that lay just beyond the threshold. Or, as Tananarive Due puts it, “Black History is Black Horror.”

The other layers of symbols that I want to draw attention to are the ones surrounding Tom. He is a trickster who travels freely, often using his clothing/garments as a key to allow safe passage. He is connected with music, and in his first iteration, he is at his most powerful when he learns ancestral conjure magic from his father. These identifying markers associate him with the traditional African American folk hero High John the Conqueror. Zora Neale Hurston is generally recognized as the first person to write about High John the Conqueror, pulling him out of the oral tradition and into print.

High John himself is a complicated figure with numerous interpretations. However, in the United States, he embraces cunning over violence, spiritual transcendence as revolutionary, and remains unconquered and unbroken even when chained. Regardless of his cunning and ability to adapt to shifting circumstances, Tom does not remain unbroken, and when he breaks, he turns to the other form of power his father left in his hands. In this transformation, we see Tom begin to resemble the Orisha. High John is identified with Eshu, a trickster who shares many of High John’s features but whose nature also vacillates between a benign trickster guide and a baneful, bloody-handed force of devastation.

The use of Tom’s experience to give the reader a personal story that echoes the historical context and links us not only with African American oral tradition but reaches back to its deeper African roots throughout the narrative is a masterclass in the principles of Afro-futurism. Doing all of this within a story that uses Lovecraft’s mythos and worldbuilding with an eye to his complicated legacy allows this accomplishment and the story’s themes to shine all the brighter.

Zin Rocklyn’s Flowers for the Sea is a work that was inspired directly by The Ballad of Black Tom. Set in an unknowable time and place in some other world during the aftermath of an endless flood. The Intradiluvian backdrop for the story also makes it a spiritual successor to Black Tom, wrestling with and embracing the previous work’s eventual outcome. Like LaValle, Rocklyn uses the story’s dedication to orient us as readers, “To Courtney, for teaching me that my anger is a gift.” This message was bound to resonate with and comfort many Black people during the post-Obama era and the rising tide of white nationalism that came with it. When facing betrayal, anger can be a gift because, unlike sadness, it pushes outward against the world rather than inward against the heart.

In Flowers, Rocklyn turns this core of anger into a tool for building a work of art that captures the imagination and recontextualizes unimaginable, untamable anger as something that can sustain just as easily as it can destroy

When I asked Rocklyn how they interact with the problematic legacy of cosmic horror, the answer was simple: “I’ll read something and know I can do it better.”

This well-earned confidence is fully displayed in the piece’s lyrical and haunting prose. Prose that, like Lovecraft’s, emphasizes the alien and dreamlike state the novella uses to great effect as we shift between past, present, and oracular visions of the future. Flower’s prose also brings it right up against, if not directly into, the tradition of epic poetry. Like Byron, Rocklyn weaves together anger, violence, eroticism, and liberation. “I kinda want to scare my readers and then make them horney.” Rocklyn is comfortable wearing the mantle of a modern-day Black Byronist, linking their work to a literary tradition in African American poetry inspired by Byron during the eighteen hundreds.

Thematically, Flower’s is a piece in deep conversation with intersectionality, aiming its rage at the patriarchy and systemic racism, two systems of oppression that feed off and support each other. Using the mythic space the story occupies, Rocklyn takes the reader through an inversion of the primeval history of the Book of Genesis, forging a new cosmology where Iraxi, in the role of Eve, step by step unwinds the fall and returns to paradise, removing herself from the clutches of the patriarchy and the tools it used to oppressor her like shame.

Right alongside their use of the flood as a means of contending with the patriarchy, Rocklyn also uses this setting to weave in themes of the middle passage and race-based oppression. Iraxi is forced to remain below deck for extended periods, valued only as a body, not a person, and is a victim of genocide. Like LeValle, Rocklyn also uses their commentary on history to show the persistence of violence within America’s racial caste system, with symbols that directly evoke the recent uptick of church burning with the resurgence of the white power movement.

This exploration of intersectionality extends to the characters within the narrative who represent the many faces of oppression. A physically dominating misogynist, a passive bystander, and an insidious female misogynoir who assures Iraxi she is an ally when, in fact, she is anything but.

Rocklyn’s method of blending biblical patriarchy, the colonial trade in human bondage with the many-tentacled creatures that lurk beneath the waves to deliver a piece that revels in celebrating the very thing that traditional cosmic horror fears is an astounding accomplishment.

I won’t be unpacking In the Palace of Science like I did these two other works of Afro-Cosmicism; with new work, it’s best to step back and hold that place of discovery for the readers. However, I will share the two men whose lives most inspired the piece.

The first is Lewis Latimer, the often-overlooked designer of the improved carbon filaments for light bulbs. His work on the light bulb’s design produced a dramatic increase in luminosity along with a sizable extension of lifetime hours. These practical and functional improvements were absolutely necessary for their mass market adoption.

The second is Thomas Washington Talley, the first Black chemistry professor to teach at a major American university and the collector of two formative volumes of African American oral folktales. I used Talley’s work, specifically the forwards to his volume The Negro Traditions, in the development of the narrator’s voice as a scientist and scholar with a keen sense of race and class consciousness informing his oral performance.

Both Latimer and Talley are men with noteworthy accomplishments who nonetheless faded into insignificance because they lived within a dominant culture that made no room for their excellence to be celebrated. The mythologizing of Edison erased Latimer’s contributions, while Talley’s achievements as a folklorist disappeared into the shadow of Chandler Harris.

The power of Afro-cosmicism comes from an understanding that beneath the apparent conflict between Afro-futurism and cosmic horror, there is a deeper truth. Lovecraft’s fears, as explored in cosmic horror, often boiled down to the possibility that someone like him would become a victim of something akin to the horrors and degradations that the global majority faced as a result of Western imperialism. That Lovecraft could be rendered as insignificant as Latimer and Talley were to the history books by forces far beyond his control. In this, the writers of Afro-Cosmicism have found a deep well of resonance to draw from that uses the symbols and concepts from both of the traditions they are working in to enhance rather than diminish when deployed within the same narrative.

While the sub-genre of Afro-Cosmisicm is not exactly new, tracing its roots to the work of the mother of Afro-futurism, Octavia Butler, it has assuredly picked up steam in recent years. With writers like N.K. Jemisin, Victor LaValle, Donyae Coles, P. Djéli Clark, and Zin Rocklyn leading the charge, it is quickly becoming one of the most exciting spaces within the speculative fiction landscape.

Chris Campbell <@chriscampbell.bsky.social> is a speculative fiction writer whose words have appeared in FIYAH, Nightlight, and khōréō. His first story for Asimov’s is an homage to Lewis Latimer, the often overlooked designer of the improved carbon filaments that made light bulbs both practical and functional, and Thomas Washington Talley, the first Black chemistry professor to teach at a major American university and the collector of two formative volumes of African American oral folktales.