by Siobhan Carroll

Professor Siobhan Carroll recounts her disappointment watching the contentious Star Trek: Voyager character Chakotay, and describes how the missed opportunity he represents helped inspire “In the Splinterlands the Crows Fly Blind,” her story from our [January/February issue, on sale now!]

The roots of “In the Splinterlands…” can be traced to my youthful hobby of Getting Mad at TV Shows. Specifically, it can be traced to 1995, and the debut of Star Trek: Voyager, for which I was psyched.

As a teenager I liked Star Trek shows (good!) and had an unhealthy fixation on maritime disaster stories (worrying!), so Voyager seemed like my kind of show. Its promo materials promised a story about a lost Starfleet ship (great!) captained by a woman (even better!) and showed a crewmember with a tattoo on his face (badass)!

Unfortunately, the show never lived up to my hopes. In retrospect, the storylines my teenage self wanted from Voyager (Mutiny! Survival cannibalism! A musical episode about a murder trial!) would have been a poor fit for Star Trek’s shiny moral universe.

Even so, I got mad at the version of Voyager I did see. One of the things I was maddest about was Chakotay: the character with the badass facial tattoo and cool name, who’d been sold as being the first Native American character in the Star Trek universe.

(Caveat: I didn’t watch Voyager steadily after it made its debut. My memories of the show are garbled, blurry, and highly inaccurate. All the better for a blog post, right? Let’s go!)

Commander Chakotay was played by Mexican-American actor Robert Beltran. Beltran tried his best, but his dialogue was just… bad. One speech Chakotay gave sounded indistinguishable from the “ancient wisdom” handed to me by an aging white hippie at the bus stop. Another time, Chakotay sounded like a character from Dances With Wolves. I remember thinking that if a character on Star Trek was talking like a character from a movie set in the 1800s, something was wrong.

Worse, Chakotay wasn’t just a “Native American” officer. He was a Magical, Mystical Native American who could Commune with Nature. Even as a white kid in the suburbs, this struck me as an obvious stereotype (and therefore “bad”).

Still, even “bad” stereotypes could sometimes work out for characters on ‘90s TV, where there weren’t a lot of great roles for actors-of-color to choose from. Sure, it was a stereotype to have Asian-American characters know kung-fu, but at least it meant that whenever a fight broke out, your favorite character would get screentime. They’d be part of the story.

But Voyager was set in the VOID of OUTER SPACE. How much “Communing with Nature” could Chakotay possibly do?

As the show waned on, Voyager’s writers seemed to struggle with this problem. They tried to create moments where Chakotay’s powers would come in handy (maybe the ship encounters a planet of trees!) but at best those plots reduced Chakotay to a messenger for the alien-of-the-week.

I remember thinking that if a character on Star Trek was talking like a character from a movie set in the 1800s, something was wrong.

More often, he was reduced to a dispenser of wisdom. In Magical Minority mode, he’d weigh in on Captain Janeway’s decision with a series of platitudes (which in my memory often turned on caring for the environment, or “honoring the land”) and she’d nod, and make her choice. Usually, it was the choice we already knew she’d make.

Because here’s the thing about ‘90s Star Trek captains. They were already the Good Guys. If Janeway had been, say, Moby Dick’s Captain Ahab, or even the historical Captain Cook (the model for TOS’s Captain Kirk), Chakotay’s advice scenes would have had real tension. But given that Chakotay never caught Captain Janeway dropkicking baby seals across the deck, his advice felt less like advice, and more like an affirmation of shared values.

When Chakotay was called on to use his powers, he’d go into a room and meditate, taking a Timeout from the plot. I don’t think he ever ‘tried and failed’at communicating with the ancestors, or the aliens, or space-trees. If the writers had written things differently, one of the magical Star Trek computers could have delivered the same information. In such scenes, Chakotay didn’t have a story: he had a function.

And that bothered me. It bothered me that they’d made this cool-seeming character into a stereotype with nothing to do.

One day, when I was watching an episode where Chakotay was stuck in a nothing-plot and the engineer was trying and failing to save everybody. I was struck by how typical this was. With the exception of DS9, Star Trek stories turn on the fact that the spaceship moves. When the ship can’t move, or the Warp Drive does something wacky, it’s a Problem. Watching this episode, I figured that the writers could eliminate most of the other positions on Voyager (including the captain) and the show’s storyline could continue. But the engineer? The engineer was necessary.

So why hadn’t they made Chakotay one of the engineers? Then he’d problems to solve every week.

That’s when it dawned on me that I’d never seen a TV show or read an SF story with a “Native American” character who was an engineer, or a hacker, or even a “student good at math.” Science fiction could imagine a lot of things, but most “indigenous” characters I’d encountered in the genre were futuristic versions of guides, trackers, warriors, or mystical gurus.

So I put a mental pin in the idea. I decided that, one day, I’d write about an indigenous character who was good with technology.

Years later, I found myself recalling my issues with Chakotay when I heard that Voyager’s “Native American” consultant had been Jamake Highwater. If you haven’t heard of him: Highwater was an Eastern European man who parlayed a fake indigenous identity into a Hollywood career. This had given him significant influence over Native American representations in film and TV.

As it happened, I’d just encountered a string of figures like Highwater in my nerdy historical reading. I’m not talking only about white men “playing Indian”, but ones who helped create the stereotype of what Shepard Krech III had called “the Ecological Indian”.

The “Ecological Indian” is a warmed-over Noble Savage stereotype: a born conservationist with deep spiritual ties to Nature, and thus a useful guide for white people looking to mend their environmental ways. Figures falling into this category included Iron-Eyes Cody, the Italian-American actor who played the “Crying Indian” in Keep America Beautiful’s famous anti-littering commercial. There was also Grey Owl, the Englishman who posed as a First Nations chief in the early 20th Century as he argued for the conservation of the environment.

And then there was “Chief Seattle”: not the real nineteenth-century Chief of the Suquamish people, but the version I’d seen quoted on posters since I was a kid, who’d given a famous speech about how the Earth was everyone’s mother. That speech was written by Ted Perry, a white scriptwriter working on an environmentalist movie funded by the Southern Baptists. (Perry later claimed he’d wanted his name on the speech, but was told his words just sounded better coming from a nineteenth-century Native American.)

The Chief Seattle speech illustrates one of the big problems of the “Ecological Indian” stereotype: the trope pretends to listen to indigenous peoples while erasing their actual concerns. Chief Seattle had given a famous speech about the land in the nineteenth century, but he was arguing for the right of “visiting at any time the tombs of our ancestors” on Suquamish territories. In short, it was a speech about land rights. Perry and the movie promoters erased this context when they remade Chief Seattle into a 1970s environmentalist.

As Krech pointed out in a follow-up to The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (1999), the “Ecological Indian” trope created problems for indigenous people who “failed” to measure up to this stereotype. Groups that wanted to build infrastructure on their lands, or sell mineral rights, were taken to task by environmentalists for not being the “right kind” of Native Americans (or First Nations people). As Gregory D. Smithers noted of a landfill case, “white farmers, ranchers, and environmentalists insisted they knew what ‘authentic’ Indians would do”.

The “Ecological Indian” trope also performed work within indigenous communities, for good and ill. As Darren J. Ranco argued in his critique of Krech, many communities made use of the trope in the context of colonialism. In some cases, the “Ecological Indian” trope had helped bands regain stewardship of their traditional lands. However, as Kimberly Tallbear argued, the “Ecological Indian” was sometimes deployed within indigenous communities as a “narrow, generic, and romanticized view of what is traditional” that fomented community divisions.

So, it’s complicated. Nevertheless, when I ran across “Ecological Indian” discourse in grad school, it was clear that Chakotay checked a lot of Krech’s boxes. His speeches endorsed the same abstract environmentalism as the 1970s Chief Seattle poster; he didn’t seem to come from a particular tribe or place; and he was often stuck giving “advice” that reaffirmed his audiences’ values. So, in addition to writing a character who was good with technology, I figured I was now on the hook for writing a character who was bad at Nature.

Some time after I wrote my “Airwalker” for Asimov’s, I saw Rebecca Roanhorse’s tweet (or maybe a quote?) about indigenous peoples not being afraid of apocalypses because they’d survived so many of them already. That got me thinking about my own postapocalyptic multiverse and how various indigenous groups might be faring there. And I figured it was time to write my engineer’s story.

My way into Charlie’s character was via the character’s feeling of mismatch and failure. I can’t tell you what it feels like to belong seamlessly to a community, but I know what it feels like to not quite fit. And I have some knowledge of what it feels like to “fail” at “properly” being an identity you were born into: an identity you didn’t choose. When that happens in the context of colonialism, it’s particularly painful.

On Voyager, as I remember it, Chakotay seemed to have an easy, seamless connection to his ancestral past. Maybe that’s true for some indigenous people, but not for all.

When I met local Lenape chief Dennis Coker at an event some years ago, one of the first things he said to me was, “Please don’t ask if I have ‘Traditional’ Ecological Knowledge; I don’t. Your people destroyed it all.” If we think of ecological knowledge as it’s depicted in Chakotay’s visions—a kind of resource that can be seamlessly transferred from past to present—that’s true. If we think of it as like Anishinaabe scholar Deborah McGregor does, as a way of living oriented toward the environment of the present, it thrives.

So these are some of the things I was thinking about when writing “Splinterlands.” (And Jurassic Park, and crow language, and Ray Bradbury, and Darrel J. McLeod’s Mamaskatch, Tommy Orange’s There There, and the history of Kahgegagahbowh. Thanks again to all my readers—particularly John Bird— and to the contributors to projects like the Online Cree Dictionary and the nēhiyawak language experience.)

Finally, a word on Chakotay. Much as that character annoyed me in the 1990s, I’m sure there are people who loved that character, including some Native American and First Nations viewers who were happy to have a character like Chakotay on screen, even if he was played by a Mexican-American, even if he spoke in clichés.

I’m also sure that some viewers loved Chakotay for a more fundamental reason: because that character said or did something that resonated with them at an important time in their life. And afterward, that thing he said became a principle they adopted, or a thing they aspired to be.

The fact is, there are times in our life when fictional characters offer us a way to imagine ourselves in the world. They help us discover who we are. This is one of the gifts of fiction.

However problematic or complicated you later feel an impactful story or character is, the fact remains: for you, it was the right story at the right time. And the more possibilities we envision for characters, the more that experience may be shared by others.

For me, the character of Chakotay helped me think about a character I wanted to write about in the future. I’m glad for that. I’d be delighted if any of the stories in this issue of Asimov’s do the same for you. And if not, I hope at least that you are enjoy them and the worlds we’ve created.

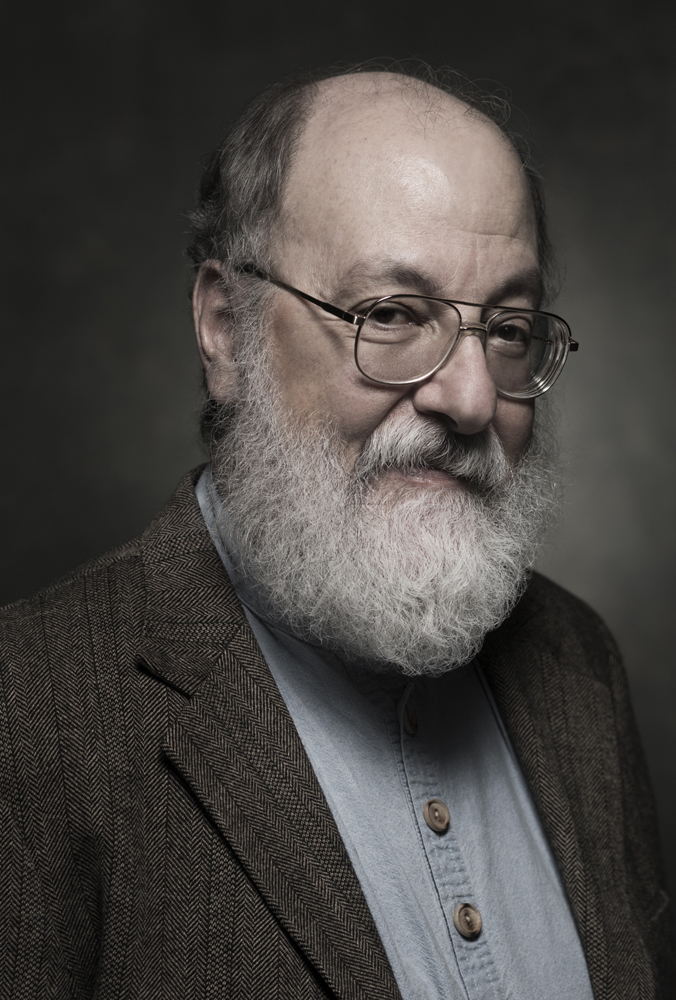

Siobhan Carroll is an associate professor of English at the University of Delaware, where she researches the literary history of empire and the environment. Her short stories can be found in magazines like Reactor and on her website at voncarr-siobhan-carroll.blogspot.com. A previous story in the Unsettled Worlds, “The Airwalker Comes to the City in Green,” appeared in the December 2019 edition of Asimov’s.